“Research, when writing a novel,” says Margaret Muir, “May be time-consuming but it is an interesting journey to be on. Usually, it means delving deeper into a subject than necessary. But once embarked on, the search for facts becomes compulsive, resulting in an accumulation of information in excess of what is required. Such was the case when I began investigating crime and punishment in the Royal Navy, in particular the Articles of War – the strict rules that regulated the behaviour of men aboard His Majesty’s ships. Rather than tossing the excess information away, I offer it as an example of where research can lead.”

Crime and punishment according to law

Every such person…shall suffer death

by M.C. Muir

The first laws of the sea were prepared by Richard the Lionheart for his men heading off on the crusades. The Ordinance or Usages of the Sea of Richard 1, the Lionhearted was recorded in the 13th century. According to these regulations:

He who kills a man on shipboard, shall be bound to the dead man, and thrown into the sea; if the man is killed on shore, the slayer shall be bound to the dead body and buried with it.

Anyone convicted by lawful witness of having drawn his knife to strike another, or who shall have drawn blood of him, he is to lose his hand.

Anyone convicted of theft shall be shorn …; boiling pitch shall be poured on his head and he shall be set ashore at the first land the ship touches.

From this early set of ordinances, the Black Book of the Admiralty emerged in the 15th century. The punishment, according to the Black Book, for the first offense of sleeping on watch, was mild. The sailor suffered a bucket of sea-water to be poured over his head. But if caught for a fourth time, the punishment usually proved fatal.

The offender was slung in a covered basket hung below the bowsprit. Within this prison he had a loaf of bread, a mug of ale and a sharp knife. An armed sentry ensured that he did not return aboard if he managed to escape from the basket. Two alternatives remained – starve to death or cut himself adrift to drown in the sea.

The Articles of War, formalized by an Act of Parliament in 1661, were based on this old Admiralty code of discipline and apart from some amendments made in the 18th century much of the content, and the brutal punishments they carried, remained the same throughout the age-of-sail.

As readers of nautical fiction are aware, the penalty for many minor misdemeanours, as well as serious offenses, carried the death penalty. Crimes ranged from abusive behaviour, negligence of duty, disobeying orders and mutiny, and the Articles of War applied equally to the lowliest ship’s boy as to the senior naval officers. Every man aboard ship was reminded of them on a regular basis – usually on a Sunday following the public Worship of God Almighty, which was also stipulated in the Articles.

While crimes and subsequent punishments at sea seemed exceedingly harsh, in 1800, the courts in England listed hundreds of minor offenses that were punishable by death. Crimes ranged from common assault, to burglarizing, to stealing a loaf of bread. For the lucky ones – mostly young males, a plea for clemency resulted in the sentence being commuted to transportation to the colonies – over the seas and beyond the seas. However, for some, enduring years of depravity in chains and subjected to the lash, resulted in a lingering death.

On land, death at the end of a rope usually came as the result of asphyxia. With a short drop through the trap door (the long drop was not introduced till later), the noose tightened but failed to separate the vertebrae, failed to cut off the blood supply and therefore failed to cause unconsciousness. Depending on where the rope was placed around the man’s neck, the victim gasped for breath as his neck muscles attempted to protect his windpipe from being crushed and the root of his tongue being forced further up his throat.

Writhing in mental if not physical agony, it could take up to half-an-hour before a man was declared dead. Hence the body was left dangling for that time to ensure the hangman had done his job satisfactorily. It was not unknown, on land, for friends of a condemned man, or members of his family, to leap forward and pull down on his feet in order to tighten the noose and hasten his demise.

At sea, the most common punishment for a man sentenced to suffer death was to be hung from one of the upper yards. This was done by reeving a sturdy rope through a block on the end of a yardarm. After his hands were tied behind his back and his ankles lashed together, the condemned man was then blindfolded or hoodwinked and a noose placed around his neck. The slack on the other end of the rope was taken up by a dozen men – often the worst types on board, and when the signal was given, the drums rolled, a gun was fired and the line was hauled lifting the condemned man from the deck and up into the rigging. Once aloft, the signal was given to belay hauling and secure the line to a pin on the rail.

With the body jerking, the face livid, the eyes and the tongue protruding, the assembled ship’s company continued to observe until the writhing stopped. However, to make sure the man was dead, his body remained hanging in the rigging for half-an-hour before it was lowered to the deck. After examination by the ship’s doctor, confirmation of death was pronounced.

But hangings were not a punishment which could be meted out by a single captain. For crimes which carried the death penalty a Punishment Warrant from the Admiralty or a Court Martial had to be convened. Without this body of senior officers to hear the case, captains were limited in the punishments they could deliver aboard their ships. Floggings, therefore, were a common form of shipboard punishment.

During the Nelson era, according to Admiralty regulations, one dozen strokes of the cat o’ nine tails was the maximum that could be given. Some captains appear to have ignored this ruling, while others were loath to flog their men arguing that it bred hatred and did not foster respect.

The barbaric sentence of being flogged around the fleet could only be delivered by a Court Martial. The result of such a cruel punishment was tantamount to a death sentence, plus it guaranteed a far more painful death than the short drop from the gallows.

When a man was sentenced to such a punishment, he was delivered into a ship’s boat in which a frame had been erected. With his hands and feet lashed to the frame, the victim was rowed to every ship of the fleet where a Bosun’s mate would inflict the prescribed number of lashes. The addition of a left-handed flagellator, approved by some sadistic captains, created a criss-cross pattern of stripes drawn by the leather thongs on the victim’s back.

The doctor, attending the proceedings in the boat, was not on hand to halt the punishment, but to advise if and when the man was dead. In some cases the floggings were continued on a lifeless corpse.

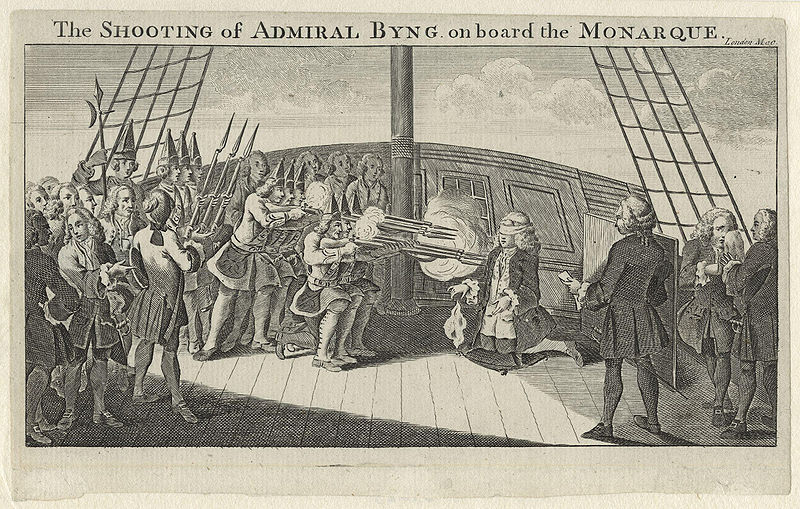

A speedy and far less painful exit from this life could be achieved when sentenced to death by shooting. One such sentence was carried out in 1757. The findings of a British Court Martial determined that Admiral John Byng, while serving in the Mediterranean, had contravened one of the Articles of War. He was accused of failing ‘to do his utmost’ to defend and hold the port of Minorca, which, as a result, was taken by the French. Byng’s argument, that his fleet had been poorly supplied by the Admiralty and was under-manned, was ignored and pleas for clemency were rejected by King George ll. Admiral Byng was taken aboard HMS Monarch in the Solent, and in front of his own men and the company of other ships, he knelt on the quarterdeck and was summarily executed by a firing squad.

Byng’s only consolation was that this mode of punishment provided him with a quick death, whereas men put ashore on a deserted island or cast adrift in an open boat faced a lingering death – death from exposure, thirst, starvation, and eventual madness. The events surrounding the life of Alexander Selkirk were famously fictionalized by Daniel Defoe in his book Robinson Crusoe. Cast ashore, after arguing with the captain, on Juan Fernandez Island in the Pacific Ocean, Selkirk did not die, as most expected, but survived alone for several years.

In other circumstances, when sailors found themselves adrift following the sinking of their ship, the survivors adopted the role of judge and jury, and passed sentence on the first unlucky victim who was to be slaughtered and eaten. Cannibalisation is not uncommon in the annals of history and if survivors were eventually found, their only defense was to quote the unwritten law of the sea. In his book, The Custom of the Sea, Neil Hanson quotes dozens of recorded incidences of cannibalism.

Finally, the most diabolical sentence handed out aboard ships of various nations was keel hauling. While it was not a death sentence per-se, it invariably resulted in the sailor’s relatively quick but cruelly painful demise. Rigged on a line that was run below the ship’s keel, the victim’s hands and feet were tied. The rope around his chest tightened as a group of sailors hauled him from the deck, dropped him into the water and pulled him under the vessel. As he was dragged across the barnacle-encrusted hull, the razor-sharp shells ripped the skin from his face, arms and body. The more months the ship had been at sea, since its bottom had been scraped, the more lethal the punishment it provided. If the victim did not drown in the process, he did not survive long from his shocking injuries. Keel hauling, in the Royal Navy, was discontinued in 1720 but continued until 1750 in some other European navies.

For any man who would suffer death at sea, death on the gun deck from an enemy’s broadside was a far sweeter alternative to being punished according to the Royal Navy’s Articles of War, which changed little over the centuries.

***

For material used in this article, my thanks go to Wikipedia and Customs of the Navy.

M.C. Muir is the author of The Oliver Quintrell Series – Under Admiralty Orders. Floating Gold, book one of series, is free on Kindle for three days, February 17-19, 2014, coinciding with this guest post. The books are available separately, and the trilogy as a boxed set on Kindle.

M.C. Muir is the author of The Oliver Quintrell Series – Under Admiralty Orders. Floating Gold, book one of series, is free on Kindle for three days, February 17-19, 2014, coinciding with this guest post. The books are available separately, and the trilogy as a boxed set on Kindle.

“Like” Muir’s Floating Gold page on Facebook, to keep up with future books in the series, and special offers.

Upcoming events: Margaret Muir will be on two author panels at Tasmania’s Festival of Golden Words March 14-16.