Spouses and lovers are more than muses.

Sometimes they function as silent partners in the creation, freely allowing their mate the needed time and space to work. As silent partners they can provide insight, critique, emotional support — and sometimes financial support. Most importantly, spouses and lovers believe in their partner’s vision, honoring the essence of their work and the need to produce it.

Sometimes spouses and lovers are artists in their own right.

When Helen Hollick invited me to join a fleet of bloggers hosting the author Kimberley Jordan Reeman on my Sea of Words, I naturally jumped on board. Admittedly, I wasn’t familiar with her name or her writing. Her husband, the late Douglas Reeman, was a well-respected author of historical naval fiction whose Georgian era Bolitho series I was familiar with. I wanted to learn more about the late Mr. Reeman’s life and inspirations, certainly — but I was equally curious about Mrs. Reeman’s writing. And I wanted to know how she and Douglas may have worked together and influenced one another during their years together.

Kimberley Jordan Reeman

A spouse can make or break a writer in so many different ways. Wives and husbands are seldom given their due credit, save a thanks in the author’s introduction or afterword. The work we produce is our own, yet it is always influenced by others, especially those we love and depend on. I asked Kimberley about her writing relationship with Douglas. Had they influenced each other? What role had she played in his prolific writing and publication? While I waited for her to write her guest post for Sea of Words, I delved into her fiction –a surefire way to get intimate with a writer’s mind and heart.

Reeman’s Coronach is an ambitious novel, deeply felt. The word coronach (I had to look it up) is a song of lamentation for the dead, often played on the bagpipes. Wikipedia defines it: “A coronach (also written coranich, corrinoch, coranach, cronach, etc.) is the Scottish Gaelic equivalent of the Goll, being the third part of a round of keening, the traditional improvised singing at a death, wake or funeral in the Highlands of Scotland and in Ireland.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coronach

Already my skin is tingling and my heart beats like a bodhran. Yet Reeman’s Coronach is not contained within an island, nor does the song end on the moors of Culloden.

Whereas Douglas Reeman set his fiction at sea, Kimberley Reeman crosses seas in her novel. Her writing is at once muscular yet rich; brutal yet exquisite, peopled with complex men and women in conflict. I am in the midst of reading it right now, enjoying it, yet at times drowning in it. Coronach is definitely not To Glory We Steer, the opening novel of Douglas Reeman’s Bolitho series — written under the name Alexander Kent This series, as all of Reman’s nautical books are admired for their perceived verisimilitude in capturing the world of the Royal navy. His portrayal of shipboard life is generally credited to Reeman’s own experience in the Royal Navy, beginning in World War II, a sixteen-year-old midshipman. He served aboard destroyers and torpedo boats in the North Sea, the Atlantic, and Mediterranean campaigns. Reeman held a variety of jobs after the war, returning to active service when the Korean War broke out. In 1958, having published two short stories, Douglas wrote the novel Prayer for the Ship, published in 1958. Ten years later the first of his Bolitho novels was published, beginning the exploits of Richard and Adam Bolitho, under Reeman’s pen name, Alexander Kent. More about Douglas Reeman/Alexander Kent’s work at douglasreeman.com

From the opening page I discovered Kimberley has her own voice, quite different from her late husband’s. She writes of men and women in tumultuous times of revolution, delving into their hearts and minds to expose what drives them. It’s not always pretty but it is vividly imagined and voluptuously written. The raw emotions, the consequences, are as real as the history behind it.

Women as muses, women as lovers, women as editors, and women as wives have long been influencing male writers and are seldom recognized, except in a dedication or an end note. Certainly the reverse may be true. I asked the author of Coronach about her working relationship with Douglas and a glimpse into his writing process – and hers. Thank you Kimberley for sharing this with us. Readers and writers — enjoy and be inspired!

THIS DARK WISDOM

written by KIMBERLEY JORDAN REEMAN FOR Collison’s “SEA OF WORDS”

Kimberley and Douglas in Tahiti, 1986. Courtesy of Kimberley Jordan Reeman.

It was a meeting of minds. It became a joining of souls. This is how it began.

Once upon a time (because all fairytales begin with these words) on a Saturday morning in Toronto, a young, aspiring novelist stood in her local library with a battered paperback in her hand. Its title was Signal⸺ Close Action! and she had never heard of the author, Alexander Kent. And because since her teens her mind had been as much in 1746 as in the real world, she said to herself, possibly aloud: “I wonder if this guy really knows how to write about the eighteenth century.”

I checked the book out. I read it. He did. I was hooked.

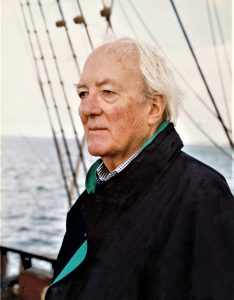

Douglas aboard the “Cutty Sark,” 1968; Courtesy of Kimberley Jordan Reeman.

Fast forward to the evening of June 6th, 1980, at Toronto’s Harbourfront cultural centre. Alexander Kent, whose real name was Douglas Reeman (I had always sensed ‘Alexander Kent’ was a pseudonym) had just read aloud, over the sound of rain drumming on the roof of the aptly named Brigantine Room, the first chapter of A Ship Must Die, the book he had come to Canada to promote. He had spent the day doing radio and television interviews, mostly talking about D-Day, and he hated reading aloud, although in years to come he would read the day’s work to me, doing all the accents, without any compunction or shyness. Then he finished reading, and the publishing representative said to the audience: “Any questions?”

There was a long silence, and I thought, it’s now or never, and stood up and said, “At the end of The Flag Captain, Richard Bolitho is obviously romantically involved with Catherine Pareja. And then when we get to the next book in the series, there’s no mention of her. Whatever happened to Catherine Pareja?”

If he was tired at the end of what had been a grueling day, he didn’t show it. He looked down at me kindly from the stage, over his reading glasses, and said in that beautiful voice of his, “I don’t know. I haven’t written the book that goes between those two yet.”

He would always say afterwards that I was the only person who had ever asked him a question he couldn’t answer.

He invited me to write to him and gave me his address, not the address of his publisher in London but that of this beloved house where I still live. We wrote to each other for four years, and gradually our friendship deepened: my letters sustained him after the death of his wife in 1983, when he fell into a black spiral of depression that almost cost him his life. He was invited to act as technical adviser on the set of “The Bounty”, then filming in French Polynesia. He made the punishingly long flight to Papeete and, not liking the situation on set when he got there, recklessly flew home three days later. As a result, he developed a deep vein thrombosis, which became a pulmonary embolism. It could have killed him.

I knew. I don’t know how I knew, but I sensed very strongly that there was a crisis, and when his next letter arrived confirming what had happened I think I cried with relief. I was already keeping his letters under my pillow, and now they began to arrive with such frequency that the woodsy scent of the desk drawer in which he kept his stationery still clung to the pages.

Douglas aboard the “Grand Turk”, Spithead, 2005; Courtesy of Kimberley Jordan Reeman.

On the evening of July 9th, 1984, four years after our first and only meeting, he walked across the lobby of the splendid old Royal York Hotel in Toronto and opened his arms to me. Later that evening, he asked me to marry him.

We were married in St. James’s Cathedral in downtown Toronto on Saturday, October 5th, 1985, and were inseparable for the rest of his life.

He used to say we lived in a house full of flowers and music. It still is, as I cut my roses in the summer and, in their season, the flowers of spring and autumn. And there is music again, although still some I can’t bear to hear. But it was also a house full of laughter. He was romantic and sensitive and easily hurt, and a chronic worrier, and as devoted to his work as I am to mine, but he had a wonderful sense of humour, too, and he was very, very funny. He loved good wine and good conversation and the company of friends: he loved me and our home and our cats: he was a man’s man and a woman’s man, with a genuine respect and understanding. I never felt that he regarded me as anything but his equal.

What did I mean to him? Let me quote him, in conversation with George Jepson of “Quarterdeck” magazine.

What role does Kim play in my work? The same role she plays in my life. She is everything to me. She edits, writes the blurbs, takes the author’s photos, does the Bolitho newsletter with me, shares the research and the ship visiting and the PR and signing sessions, handles the computer side of things and the e-mail. She is my right hand and partner in everything I do, as well as being a hugely talented writer. As I said in the dedication to her in my latest book, written under very difficult circumstances, I couldn’t have done it without her.

And so, like the fairy tales, we did live happily ever after, until the end. There is always an end.

In the movie “Lady Hamilton” a young streetwalker asks the destitute Emma Hamilton, who has fallen, as she did in reality, into a vortex of alcoholic depression after the death of Horatio, Lord Nelson, “What happened then? What happened afterwards?” Vivien Leigh as Emma, with immense poignancy, conveys the absolute nadir of grief when she answers, “There is no then. There is no afterwards.”

But there is. The black tsunami of grief overwhelms you, and you never know what’s going to cause it: a time of day, an angle of light, a room, a forgotten photo falling out of the pages of a book, certain music, a significant date. It will take you and break you and drive you to your knees, until you think there will never be an end to it, that your heart, now broken, can never shatter again, and yet it does, again and again. And this pain, this mourning, this giving of your heart to be splintered because you loved, confers a dark wisdom: a knowledge of life and death. You have crossed a river of shadows into another country, where no one who has never yielded love to death has walked.

I brought this dark wisdom to Coronach: all my understanding of great love and great pain. I wove the story from the warp and weft of history, to tell truths more compelling than fantasy. I saw war through the eyes of a man who had lived it, and who had trusted me enough to share his experiences of it, and I brought those truths to Coronach and wrote of them unflinchingly and without compromise. I brought, I hope, compassion. And what I would hope you, the reader, take away from this book is not its darkness, which is authentic darkness, but a memory of the love, courage, honour, loneliness and human frailty of my people, whose lives become the very fabric of history.”

About the background of this epic saga Kimberley has this to say:

“It is not necessary to look further than the history of Canada, and Toronto itself, for the genesis of Coronach: a vast country explored, settled, and governed by Scots, and a city, incorporated in 1834, whose first mayor was the gadfly journalist and political agitator William Lyon Mackenzie, a rebel in his own right, and the grandson of Highlanders who had fought in the ’45. The Vietnam War, also, burned into the Canadian consciousness the issues of collateral damage and the morality of war; and from this emerged one character, a soldier with a conscience. In unravelling the complexity of his story, Coronach was born. — KJR

***

Kimberly Jordan Reeman was born in Toronto, graduating from the University of Toronto with a Bachelor of Arts (hons) in English literature in 1976. She worked in Canadian radio and publishing before marrying the author Douglas Reeman in 1985, and until his death in 2017 was his editor, muse and literary partner, while pursuing her own career as a novelist.

She has always been a spinner of tales, telling stories before she could write and reading voraciously from childhood. She cites Shakespeare, Hardy, Winston Graham and the novels of Douglas Reeman and Alexander Kent as her most profound influences. From Graham, who became a friend, she learned to write conversation, to eavesdrop as the characters spoke; from the seafaring novels of Reeman and Kent, which she read years before meeting the author, she came to understand the experience of men at war. Read more about Kimberley Jordan Reeman and her novel Coronach on the Reeman website douglasreeman.com/kim-reeman

This post concludes a tour of blogs featuring Kimberley Reeman and her historical saga Coronach. I have followed and participated with great interest. If you missed some of the ports of call and want to learn more of this writer and of her late husband, author Douglas Reeman, please sail by for a look:

4th Nov Richard Tearle Slipstream

5th Nov Ross Wilson books@nauticalmind.com

6th Nov Annie Whitehead EHFA (English Historical Fiction Authors

7th Nov Sarah Murden All Things Georgian

8th Nov Amy Bruno Passages to the past

9th Nov Anna Belfrage Stolen Moments

10th Nov Antoine Vanner Dawlish Chronicles

11th Nov Helen Hollick & Kimberley’s own blogs

12th Nov Linda Collison Sea Of Words