Beyond Lady Barbara;

Women as Portrayed in British Naval Fiction

by Linda Collison

This is the unedited draft of an article that first appeared in the November 2020 issue of the Trafalgar Chronicle. My thanks to journal editor Judith Pearson for her interest and editing.

‘Women ain’t no good on board, Jack, that’s sartain.’[1]

Frederick Marryat, author of numerous novels including Frank Mildmay, Mr. Midshipman Easy, and Poor Jack, published in 1840, from which the quote is taken, is generally recognized as the father of British naval fiction. ‘Unlike Smollett,[2] who gives us real ships but very little sense of an ocean surrounding them, Marryat provides both real ships and a real sea,’ Conrad observed.[3] A Royal Navy officer himself, Marryat wove the influence of his experiences into his novels. It is noteworthy that he frequently mentions women in his stories – women as mothers, nurses, aunts, servants, captain’s wives, steward’s wives, sweethearts, lovers. And, despite the sailor’s insouciant tone that Marryat adopts throughout his work, ever present in the background is an ‘awkward emphasis on the body, violence, cruelty and random death.’[4]

A century later, C.S. Forester further developed the British naval novel with his eleven-book series recounting the adventures of Horatio Hornblower as he rises from midshipman to admiral during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Forester, and other writers following in his wake, wove historical people, events, and nautical detail into the fabric of their fiction in such a way as to seemingly recreate an era – a mythos of naval culture featuring the individualized hero in command of a ship.

Forester’s Hornblower is a conflicted protagonist – reserved, almost secretive in nature – who deeply resents the upper class. He struggles for self-confidence, fighting seasickness as well as the enemy; he is a believable, fallible, hero. Serialized in magazines, adapted to film and television, Hornblower became a literary cult, complete with a fictional biography, The Life and Times of Horatio Hornblower by C. Northcote Parkinson. ‘I loved how after researching Horatio Hornblower for my son’s literature class that a Canadian historian went to the Nautical Museum in England looking for the Display on Horatio Hornblower, thinking that he was truly a real historical person,’ writes one Amazon reviewer of Parkinson’s faux biography.[5] The power of fiction to influence popular perceptions of history cannot be overlooked.

And what of the women in Forester’s fiction? By and large they are shown only in relationship to the main character – as wives or lovers. Maria, Horatio’s middle-class shore wife, is sketched with a few words – short, tubby, stout, gauche, apple cheeks. This is not a marriage that can provide our ambitious officer with any social advantages or interest.[6] Enter Lady Barbara Wellesley, requesting passage back to England. Forester idealizes her as an attractive, well-born woman ‘completely at ease, conversing with a fearless self-confidence which nevertheless (as Hornblower grudgingly admitted to himself) seemed to owe nothing to her great position.’ – quite the opposite of his dowdy shore wife. ‘His own Maria would have been too gauche ever to have pulled that party together.’[7] Lady Barbara is perfect – she is everything he could desire in a wife. Horatio is a humanized hero.

Amazon reviewer Mary Ann, a professed ‘Hornblower geek’ writes, ‘My only complaint was that I thought more attention should have been devoted to Maria, his first wife…The ironical thing is that I have always found her – meant to be less interesting than Lady Barbara – far more of a rounded and sympathetic character.’

Other authors imagined their own naval protagonists; Dudley Pope created the Lord Nicholas Ramage series; Douglas Reeman, as Alexander Kent, wrote the Bolitho novels. Soon the literary seas were filled with fictional frigates and officers of ‘Nelson’s Navy,’ rising through their mettle and merit, outwitting, out-sailing, and outshooting the enemy, occasionally rescuing wellborn women and wealthy countesses. Most include many mentions and cameo appearances of historical figures, and some insinuate their fictional officers into historical naval engagements. David Donachie[8] gives us John Pearce, the marine Markham, as well as fictional biographies of Admiral Nelson and Lady Hamilton in his Nelson and Emma Trilogy. Julian Stockwin[9] invents Thomas Kydd, a young man pressed into service, who makes his way ‘up through the hawsehole’ to obtain his commission. Richard Woodman[10], a decorated professional mariner, has written three naval fiction series; Nathaniel Drinkwater’s set squarely in the Nelson era. Several female novelists write Nelson-era fiction; among them are M.C. Muir’s[11] Oliver Quintrell Series and V.E. Ulett’s[12] Blackwell’s Adventures. Altogether, there are hundreds of Georgian-era naval novels, and more being published every year. Many are highly praised for their historical accuracy and their perceived realism.

And what of the Georgian females? How do novelists portray them?

Alan Lewrie, the bawdy protagonist conceived by Dewey Lambdin, writes about women in a parody of John Cleland’s ribaldry. ‘And she cried out like a virgin on her wedding night, though she writhed and clung to him like a limpet, matching his every moment…Why, dear Lord, is every woman I meet and hop into bed with as feeble in the brains as cold, boiled mutton?’ [13]

Some readers don’t want to read about sexual exploits in naval novels. A male fan of Richard Woodman’s Nathaniel Drinkwater series writes in an Amazon review, ‘The characters are all believable and very human and although there are the inevitable encounters with the opposite sex, they are believable without the Mills and Boon explicit rubbish that seem to dominate books from the lower order of authors in this genre these days.’

Just as in real life, fictional women can be more than persons in need of rescuing, bedding, or marrying. Julian Stockwin, in Tenacious, gives us Isabella, a ‘Minorquin’ who helps protagonist Thomas Kydd conceive of and carry out a plan against the Spanish. ‘She was practical and intelligent, and if anything was to be rescued of the mission it would have to be through her.’[14]

Admirals alone, cannot win a war. Without the seamen and the specialized warrants, without the craftsmen ashore, without the shipwrights, the pursers and the provisioners, ships don’t sail and guns don’t fire. Without women, it can be hard to keep a crew onboard for very long. There was a surfeit of post captains but never enough able seamen, or even landsmen, in Nelson’s navy. Whereas most authors focus on one officer as he makes his way from midshipman to admiral, Alaric Bond[15] takes a different approach in his Fighting Sail series. Instead of limiting us to the quarterdeck, Bond shows us the whole ship from the viewpoints of multiple characters; from captain to quartermaster, from purser to able seaman, from first lieutenant to the ship surgeon’s wife, he immerses the reader in the world of the ship.

Antoine Vanner[16] has ventured beyond Nelson’s Navy to Victoria’s – a time of transition from sail to steam. The Dawlish Chronicles feature Royal Navy officer Nicholas Dawlish aboard gunboats in far corners of the world, protecting Britain’s empire. Mrs. Dawlish is a motivated woman of humble origins; one who drives the action in Britannia’s Amazon, an onshore Victorian detective story paralleling her husband’s adventures at sea.

Returning to C. S. Forester’s women: Aboard Lydia, Hornblower is concerned about the comfort of Lady Barbara when action with Natividad becomes imminent. ‘The orlop meant that Lady Barbara would be next to the wounded, separated from them only by a canvas screen – no place for a woman. But for that matter neither was the cable tier. The obvious truth was that there was no place for a woman in a frigate about to fight a battle.’[17] Forester then shows us just how useful a woman could be on the orlop deck after a battle. ‘Insensibly he came to shift some of his responsibility onto Lady Barbara’s shoulders; she was so obviously capable and so unintimidated that she was the person most fitted in all the ship to be given the supervision of the wounded.’[18]

In real life, the orlop was the place for women in a frigate about to fight a battle, as primary sources tell us. Betsy Wynne Fremantle, nineteen and newly wedded, lived aboard Inconstant with her husband, Captain Thomas Fremantle. Betsy writes on 8 August 1796, ‘Sir John Jervis got us all in a terrible scrape in the evening. He went exceedingly near shore it fell calm all at once and we were all within gun shot without a possibility of getting away. The French fired from all their Batteries, the Golliath being nearest they only aimed at her luckily for us, for we were equally near and some of the shots came so near to us that C. Foley was almost tempted to send us ladies in the Cockpit.’ Betsy continues, describing how they at last got away from the shore with the help of the crew towing the ships away from the shore with the ships’ boats. Apparently, Captain Foley (Goliath) was somewhat of a bother. ‘If C.F. (Captain Fremantle) had no intention to marry me I dare say the old Gentleman has some idea of it himself. It makes me quite miserable. I hide this from Papa for he has a great partiality for C. Foley, he certainly would give him the preference. For my part as I do not think riches alone can make me happy my choice is in favour of the absent friend.’[19]

Betsy married her absent friend and sailed aboard Inconstant with him for some months.[20] Any young woman, aboard or ashore, had to deal with the hazards of childbirth. Betsy hints of her own pregnancy in the same paragraph as she relates the naval activities of the day: ‘Friday, July 21st Captain Miller came on board with 350 of the Theseus’ men they are all to land in the night but in order to keep out of sight it was late when the three frigates got in shore and day light by the time the troops were landing, they therefore returned without doing any thing, I was unwell as usual, slept below, had a woman with me the sailmaker’s wife.’[21]

Few fictional captains bring their wives aboard to set up housekeeping, but the young Mrs. Fremantle wasn’t the only woman in real life to accompany her naval captain husband on his assignment and write about her experience. In 1791 Mary Ann Parker accompanied her husband, captain of the Gorgon, a naval supply ship, on a delivery to New South Wales. She writes of finding an American schooner anchored by an uninhabited island. ‘The master, his wife, and four or five men were aboard without a grain of tea or scarcely any provisions.’ The men of the Gorgon helped the Americans hunt turtles ashore to provision their schooner. One of the children from the naval ship was buried on this same island.[22]

Transport ships regularly carried the wives and children of soldiers who were married ‘on the strength,’ and many of these females were present in some of the major fleet actions of this period.[23] These women are seldom seen in historical naval fiction, even as part of the background. We tend to forget they were ever there.

Although every naval author has his loyal fans, Patrick O’Brian is arguably the most acclaimed. His writing, his ability to recreate naval society, has been compared to that of Jane Austen. ‘The detail of the world of the ship is wonderful. It’s a complete and distinct society… It’s Jane Austen at sea,’ says Lucy Eyre of the Guardian.[24] Austen too, wrote of the navy, given that her two of her brothers were naval officers. In Persuasion we are introduced to Sophia, Captain Wentworth’s sister and Admiral Croft’s wife. Sophia Croft is a supportive wife and felt entirely at home on a naval warship. Historian Sheila Kindred proposes that the character was drawn from Jane Austen’s real-life sister-in-law Fanny Palmer Austen, who often accompanied her husband Charles aboard the 32-gun frigate, Cleopatra. Kindred details some of the naval social life in Bermuda and Halifax, pointing to the importance of the support naval wives might give to their husbands’ careers. Later, Captain Austen and his family lived aboard Namur, then a receiving vessel in home waters, where Fanny gave birth to her fourth child, and died, aboard ship.[25]

Patrick O’Brian shows us the greatest variety of women and girls – some as minor characters, some as colorful details sketched into the setting. Besides the expected wives and lovers, he gives us the spy, Louisa Wogan, the orphaned Indian girl, Dil, the convict, Clarissa Oakes, and many others. Queenie, Jack Aubrey’s childhood friend, is the historical Hester Maria Elphinstone, Viscountess Keith, born Hester Maria Thrale, a friend of Samuel Johnson. In O’Brian’s fiction the intellectual Queenie once tutored Jack in mathematics. ‘An odd pair: handsome creatures both, but they might have been of the same sex or neither. Nor was it a brother and sister connection, with all the possibilities of jealousy and competition so often found therein, but a steady uncomplicated friendship and a pleasure in one another’s company.’[26]

Such sketches of female characters who are neither lovers nor wives add both interest and authenticity to historical fiction. Chris Durbin gives us a peek at an influential woman of business, a shipyard owner at Deptford Wharf during the Seven Years’ War. Durbin says Mrs. Winter is an historic character who makes a minor cameo appearance in Perilous Shore, the sixth book in his Carlisle and Holbrooke Naval Adventure series. The writer discovered her while researching Navy Board minutes regarding the building of flat-bottomed boats for the raids on France in 1758.[27] This micro-historical detail illuminates a woman who played a role, however minor, in Britain’s naval success.

O’Brian gives us glimpses of the women of the lower deck – Mrs. James, the Marine sergeant’s wife, aboard Surprise in The Far Side of the World. She plays no part in the story, but O’Brian acknowledges her existence and in doing so, adds texture to his setting. In The Hundred Days he introduces Poll Skeeping, who had been at sea, off and on, for twenty years. Poll is a loblolly who had trained at Haslar. ‘She is up to anything in the way of blood and horrors,’ Aubrey says to Maturin, whom he frequently enlightens, along with the modern reader, about the ways of the ship. Says Poll, in answer to the doctor’s question as to how women like her came to be aboard. ‘Why, sir, in the first place a good many warrant-officers – like the gunner, of course – take their wives to sea, and some captains allow the good petty-officers to do the same. Then there are wives that take a relation along – my particular friend Maggie Cheal is the bosun’s wife’s sister… and so it went, relations in ships – I had a sister married to the sailmaker’s mate in Ajax – friends in ships, with a spell or two in naval hospitals – and here I am, loblolly-boy in Surprise, I hope, sir, if I give satisfaction.’ [28]

As for shore wives, Aubrey’s dependable Sofie is developed throughout the series, as is her volatile cousin Diana Villiars. O’Brian contrasts their opposite temperaments to good effect. Villiers is an often-adversarial character who breaks the doctor’s heart in various ways throughout the twenty-volume series. Independent-minded and impetuous, hers is the plight of most Georgian women who, by necessity, must depend on a man to survive. In Villiers,surgeo O’Brian has created a complex character who is not idealized, nor is she quite demonized.

Few other authors include warrant wives in their crew. Alaric Bond, in his Fighting Sail series, gives us a very believable one in Kate Black Manning, a merchantman’s daughter who becomes the ship surgeon’s assistant, marries him, and lives aboard for a time, acting as his assistant. Bond also includes a subplot involving Kate’s maid, who like many women of the era, turning to prostitution in hard times.

‘There was only one woman on board, the Boatswain’s wife…’[29] This, from Pope’s The Black Ship, a revealing account of the Hermione mutiny. Pope, an acclaimed naval historian, chooses not to reveal any warrant wives in his fictional series.

According to primary sources, the wives of warrants and petty officers frequently lived onboard; although not on the muster rolls, their husband’s ship was their home. N.A.M. Rodger suggests there were many practical ways in which they might have made themselves useful, and earn an income aboard, by washing, sewing, or looking after children.[30] Admiral Jervis accused them of wasting water on washing, yet the women are known to have assisted the surgeon and the gun crews during action. In any case, women were sometimes aboard. Though they have largely been ignored by the novelists, they were part of the ships’ company and as such, part of the ship’s success or its failure.

What a novelist chooses to include or ignore affects our perception of history. The art and craft of writing requires choices be made, but those choices color our collective memory of historical events. Who was important enough to include in the telling? Who is important enough to give voice to? Are some classes of people so insignificant or so repulsive as to be left out of the telling altogether?

“It was very strange that the Admiral – a religious and good man – could not bear the sight of a female,” gunner William Richardson comments in his memoir A Mariner of England 1780-1817. Speaking for the seamen, Richardson considered the Portsmouth working girls important enough to include in his story. He describes the incident aboard the 48-gun frigate Minerva having just returned to England from Bombay after a passage of three months and seventeen days. ‘As the Admiral was dressing to go on shore, he saw out of the cabin windows two wherries pulling up to the ship full of girls; he came out much agitated, and sending for Captain Whitby, desired him not to allow any such creatures to come near the ship, so they were hailed to keep off; but as soon as the Admiral got on shore they were permitted to come on board, and the ship was soon full of them.’ Captain Whitby merely waited until the Admiral was ashore before allowing the women to come aboard.[31]

Richardson also describes the day in 1806 when Her Royal Highness Caroline, consort to the Prince of Wales, visited Caesar, Sir Richard Strachan’s flagship. ‘All the girls (some hundreds) on board were ordered to keep below on the orlop deck, out of sight until the visit was over.’ But her Royal Highness had a keen eye and spied some of the girls trying to get a glimpse of her from the hatchway. ‘Sir Richard,’ the Princess says, ‘You told me there were no women aboard the ship, but I am convinced there are, as I have seen them peeping up from that place, and am inclined to think they are put down there on my account. I therefore request that it may no longer be permitted.’ The princess and her retinue were escorted back to the quarterdeck again, and the girls were set free. ‘Up they came like a flock of sheep, and the booms and gangways were soon covered with them, staring at the princess as if she had been a being just dropped from the clouds,’ Richardson relates.[32]

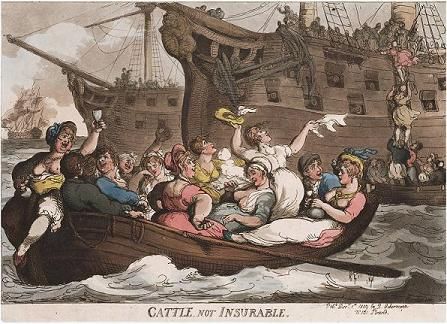

Others found the practice shocking. ‘It is well known that immediately on the arrival of a ship of war in port, crowds of boats flock off with cargoes of prostitutes… The whole of the shocking, disgraceful transactions of the lower deck it is impossible to describe… Let those who have never seen a ship of war picture to themselves a very large low room (hardly capable of holding the men) with 500 men and probably 300 or 400 women of the vilest description shut up in it, and giving way to every excess of debauchery that the grossest passions of human nature can lead them to; and they see the deck of a 74-gun ship the night of her arrival in port.’[33]

‘That no women be ever permitted to be on board, but such as are really the wives of the men they come to, and the ship not to be too much pestered even by them. But this indulgence is only to be tolerated while the ship is in port, and not under sailing orders,’ Admiralty Regulations and Instructions, 1790.’ This regulation, Robowtham says, was universally disregarded.[34]

There was not always a clear distinction between a sailor’s wife and a prostitute, historians Roy Adkins and Lesley Adkins point out. Sometimes sailors married prostitutes but often sailors’ wives were forced to turn to prostitution to survive. A seamen’s wife was not told when her husband’s ship would return or to what port, and mail delivery was not always reliable. Accompanying their husbands on board might have presented a better alternative for some who had no other means of support.[35]

The typical ship, says N.A.M. Rodger, spent less than half her time in commission at sea, but the men were still needed aboard while in port or off-shore at anchor.[36] Novelists sometimes refer to the women aboard in port as Bond does in True Colours. ‘The only exception was a prolonged period in his second ship, a third rate that had lain three months at anchor with the Wedding Garland hoisted, and all manner of women running riot throughout the crowded decks.’[37]

Robert Hay, in his memoirs Landsman Hay, describes the market-like atmosphere aboard Salvador de Mundo, a three-deck guard ship, permanently anchored in Plymouth Harbor. ‘On the lower deck, appropriated to the ship’s crew, almost every berth was converted into a shop or warehouse where commodities of every description might be procured: groceries, haberdashery goods, hardware, stationery, everything, in fact, that could be named as the necessities or luxuries of life. Even spirituous liquors, though strictly prohibited, were to be had in abundance, the temptations of the enormous profits arising from their sale overcoming any fear of punishment… As those who were of the regular ship’s crew were but few in number, and chiefly employed manning officers’ boats, it might be thought this lower deck a desirable berth, but as the greater number kept their wives and families on board, it was pretty much crowded day and night.’[38]

The gunner Richardson writes of his wife, Sarah, daughter of a master stonemason of Portsea, who accompanied him on his second assignment to the West Indies, aboard Tromp. The wives of the captain, the shipmaster, the purser, and the boatswain were also aboard for this assignment, as was the wife of the sergeant of marines and ‘six other men’s wives had leave to go.’ On August 2, 1800, he tells us, the captain’s wife was delivered of a fine boy.[39]

In Fort Royal, yellow fever overtook the ship. The shipmaster and his pregnant wife died, and the boatswain died, leaving his wife and daughter on board. When Sarah got sick, Richardson took her ashore and put her in the care of a French physician and an African nurse, Madame Janet, at his own expense. Sarah lived and William brought her back home, aboard ship.

Another memoirist clearly has an eye for the ladies; he notices them wherever he goes. At anchor in the West Indies John Nicol describes ‘the female slaves, who brought us fruit and remained on board all Sunday until Monday morning – poor things! And all to obtain a bellyful of victuals.’[40] Later, aboard a transport ship bound for New South Wales, ‘Every man on board took a wife from among the convicts.’ His was Sarah Whitlam, whom he ‘courted for a week and upwards, and would have married her on the spot had there been a clergyman on board.’ Sarah had been transported for stealing – her sentence seven years. ‘I knocked the rivet out of her irons upon my anvil, and as firmly resolved to bring her back to England when her time was out, my lawful wife, as ever I did intend anything in my life. She bore me a son in our voyage out.’[41]

A cooper like his father before him, Nicol then served aboard Goliath under Captain Foley in the battle of Aboukir Bay. He mentions the gunner’s wife as being of good comfort during the battle, bringing them both a drink of wine to fortify them. Several of the ship’s women were wounded in the action and one, from Leith, died as a result of her wounds. ‘One woman bore a son during the heat of action.’[42] Even when a woman died at sea, the death was seldom recorded. Their names were not listed in ships’ muster books, and since only those people who were mustered had any official existence, the lower deck women are largely invisible to us. Although the naval writers know their dates and admirals, although they pepper their accounts with historical people and convincing nautical and tactical detail, for the most part they ignore the great numbers of prostitutes who entertained, comforted and satisfied the desires of the men of the lower decks, shared their hammocks and their meals. Although they weren’t officially sanctioned, they were there.

Roy Adkins says, ‘During the Battle of Trafalgar, women were probably working as powder monkeys on board many of the ships, but their names are unknown because their presence was not officially recognized. The only female powder monkey of the Napoleonic Wars about which any amount of reliable information has survived is Ann Hopping, who later remarried to become Ann Perriam (also known as Nancy Perriam). She was the wife of a gunner’s mate and, although not at Trafalgar, she took part in several other major battles.’[43] Adkins quotes an article published in 1863: ‘Upon Sir James Saumarez’s subsequent removal to the Orion, Hopping and his wife followed him. Mrs. Perriam served on board the latter ship five years, and during that time witnessed and bore her part in, besides many minor engagements, the following great naval battles: at L’Orient, on the 23rd of June, 1795; off Cape St. Vincent, on the 14th of February, 1797; and at the glorious battle of the Nile, won by Nelson on the 1st of August, 1798. Mrs. Perriam’s occupation while in action lay with the gunners and magazine men, among whom she worked preparing flannel cartridges for the great guns.’[44]

British naval fiction set in the Georgian age is alive and well, some two centuries after the battle of Trafalgar, and continues to shape popular perceptions of history. A new generation of readers is discovering the genre, even as authors continue to invent new commanders, new ships, and new ways to thwart Buonaparte. Readers take part in online forums and in social media groups devoted to their favorite authors. Facebook, Reddit, Goodreads, and HistoricNavalFiction.net have many thousands of active members among them. Within the genre there are some well-drawn female characters, though admittedly, they are few. In general, women tend to be conceived as love interests for the protagonist. The scarcity of authentic women in historical naval fiction affects how we ‘remember’ our history. Ashore and aboard, females of all classes were witnesses and participants, helping or hindering the war effort, affecting the outcome. Wives, widows, servants, shipowners, merchants, princesses, prostitutes – they all played their part.

‘God bless,’ called Queenie, and ‘Liberate Chile, and come home as soon as ever you can,’ called her husband, while the children screeched out very shrill, fluttering handkerchiefs. And at the very end of the mole, when the frigate turned westward along the Strait with a following breeze, stood an elegant young woman with a maidservant, and she too waving, waving, waving…’[45]

[1] Frederick Marryat, Poor Jack (1840. Electronic edition: Gutenberg.org), end of chapter 1.

[2] Tobias Smollett (1721-1771) was one of England’s earliest novelists. In The Adventures of Roderick Random (1748), Smollett drew on his own naval service as a surgeon’s mate to produce the first significant fictional account of life on board an English warship.

[3] Elliot Engel and Margaret F. King quoting Joseph Conrad in the Victorian Novel Before Victoria; British Fiction during the Reign of William IV, 1830-37 (MacMillan Press, 1984), pg 27.

[4] John Peck, Maritime Fiction; Sailors and the Sea in British and American Novels, 1719-1917 (Palgrave, 2001.), pg 64.

[5]‘Hypermom,’A reader’s review of C. Northcote Parkinson, The Life and Times of Horatio Hornblower; A biography of C.S. Forester’s Famous Naval Hero (Ithica, New York: McBooks Press, Inc. 2005.) online amazon.com.

[6] Andreas Mügge, ‘The Romantic Side of Hornblower’, Lüdinghausen: August 2018, C.S.Forester Society, csforester.files.wordpress.com>2018/11.

[7] Forester, Beat to Quarters (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1937), pp 299-301.

[8] David Donachie, a Scottish historic naval novelist born in 1944, also writes under the pen names Tom Connery, Jack Ludlow, and Jack Cole. His novels have been published from 1991 to the present. Source: Wikipedia, David Donachie, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Donachie (accessed January 2020).

[9] Julian Stockwin was born in 1944 in England. He has published historical naval novels from 2001 to the present.

[10] Richard Woodman, born in England in 1944 retired in 1997 from a 37-year nautical career to write historic naval novels. Source: Wikipedia, Richard Woodman, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Woodman (accessed January 2020).

[11] Margaret Muir, a British author, lives in Tasmania and is a member of the Tasmanian Sail Training Association. Source: https://www.historicnavalfiction.com/authors-a-z/margaret-muir (accessed February 2020).

[12] Eva V. Ulett, an American author and book reviewer, is a member of the National Book Critics Circle and the Historical Novel Society. Source: https://www.historicnavalfiction.com/authors-a-z/v-e-ulett (accessed February 2020).

[13] Dewey Lambdin, The King’s Commission (New York, St. Martin’s Press, electronic edition), chapter 7.

[14] Julian Stockwin, Tenacious: A Kydd Sea Adventure, (Ithaca, New York: McBooks Press, electronic edition), pp201-214.

[15] Alaric Bond is a British author born in 1957 who writes books on fighting sail. His publications range from 2008 to present. Source: Book Series in Order, https://www.bookseriesinorder.com/alaric-bond/ (accessed January 2020).

[16] Antoine Vanner, author of the Dawlish Chronicles, spent many years traveling in the international oil industry prior to becoming a naval historic author. Source; The Dawlish Chronicles, https://dawlishchronicles.com/ (accessed January 2020).

[17] Forester, p209.

[18] Ibid, p252.

[19] Anne Fremantle, The Wynne Diaries; The Adventures of Two Sisters in Napoleonic Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, (1982), p217-19.

[20] Fremantle, p268.

[21] Ibid, p277.

[22] Mary Ann Parker, A Voyage Round the World in the Gorgon Man of War (New York, Cambridge University Press, 2010) pp144-145.

[23] W.B.Rowbotham, ‘Soldiers’ and Seamen’s Wives and Children in H.M. Ships,’ The Mariner’s Mirror, Vol. 47, 1961, Issue 1, pp42-48.

[24] Eyre, Lucy. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/nov/28/why-patrick-obrian-is-jane-austen-at-sea Accessed 1/10/2020.

[25] Sheila Johnson Kindred, Jane Austen’s Transatlantic Sister; the life and letters of Fanny Palmer Austen (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017).

[26] Patrick O’Brian, The Hundred Days (New York: Norton, 1999) p15.

[27] Private correspondence with Chris Durbin, author of Perilous Shore (Old Salt Press, 2019).

[28] O’Brian, p48-53.

[29] Dudley Pope, quoting the deposition of John Mason, former carpenter’s mate in the frigate Hermione, on the title page of electronic edition of The Black Ship (Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Maritime, 2009).

[30] N.A.M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean; a naval history of Britain, 1649-1815 (London: Norton, 2004), pp 407, 505-506.

[31] Spencer Childers, ed., A Mariner of England; an account of the career of William Richardson from cabin boy in the merchant service to warrant officer in the Royal Navy (1780-1819) as told by himself (London: John Murray, 1908), p110. Admiral Lord Cornwallis.

[32] Ibid, p225-226.

[33] Christopher Lloyd, quoting Admiral Hawkins, ‘Statement of Certain Immoral Practices in H.M. Ships’ in The British Seaman (London: Granada, 1968), p224-225

[34] Rowbotham, pg 43.

[35] Roy Adkins and Lesley Adkins, The War for all the Oceans; from Nelson at the Nile to Napoleon at Waterloo (New York: Penguin, 2008), p179-180.

[36] N.A.M. Rodger, The Wooden World; an anatomy of the Georgian Navy (London, New York: Norton, 1986), p151.

[37] Alaric Bond, True Colours, (Fireship Press, 2010), pg 20.

[38]Vincent McInerney, Ed. Landsman Hay; the memoirs of Robert Hay (Barnsley, UK: Seaforth, 2010), p50-52.

[39] Childers, p169-170.

[40] Tim Flannery, ed., The Life and Adventures of John Nicol, Mariner (New York: Grove Press, 1997), pg 37.

[41] Ibid, p121-122.

[42] Ibid, p174-175.

[43] Adkins and Adkins, p32-33.

[44] Roy Adkins, quoting from The Times (13 May 1863), Nelson’s Trafalgar; The battle that changed the world (New York: Penguin, 2006), p79-81.

[45] O’Brian, p281.