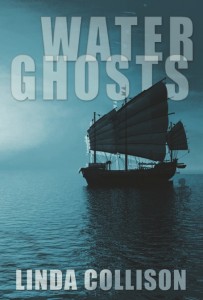

Water Ghosts

Copyright © Linda Collison 2015

Published by Old Salt Press, LLC

ISBN: 9781943404001

LCCN: 2015941395

Publisher’s Note: This is a work of fiction. Certain characters and their actions may have been inspired by historical individuals and events. The characters in the novel, however, represent the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review.

——

Under heaven nothing is more soft and yielding than water.

Tao Te Ching

——-

Water Ghosts

A novel

by Linda Collison

Chapter One

The doomed ship is set to sail at ten A.M. and I am to be aboard. The taxi has dropped us off at the marina – my mother, her boyfriend and me. They’re here to see me off.

From the parking lot I can see it. Good Fortune is unmistakable because it’s bigger than the other boats and because it’s old and foreign-looking. Three masts rise up like pikes from the rectangular deck. A tattered pennant hangs limply from the smallest one. Faded yellow silk.

I don’t want to go but Mother is making me. Walking toward it, carrying my sea bag, I already feel like I’m drowning. Dragging my feet along the rickety wooden pier, past neglected powerboats and sailboats covered with blue plastic tarps, I’m trying to resign myself to my fate. I’m trying to do what Dad used to tell me to do when I was afraid. Think of something funny! But nothing funny comes to mind.

Looking around at this run-down dockyard in an industrial park near the Honolulu International Airport I’m thinking it’s wrong, it’s all wrong. Hawaii is not paradise – at least, not for me. A jet takes off, flying low overhead, drowning us out momentarily with its thunderous roar. Mother covers her ears with her hands and squeezes her eyes shut until it passes. The boyfriend glances at his big gold watch and grins.

“Nine-forty,” he says. “You’ll be boarding soon.”

“Oh, James! It looks like an old pirate ship, doesn’t it?” Mother’s perky voice edges toward hysteria. “A Chinese pirate ship, how cool is that! You are going to have the time of your life. I wish I was going!” She continues to talk but I can’t hear her anymore. Her words are bursts of color, blinding me. I look away.

I see things other people don’t see.

The old wooden ship lists in its slip. Doesn’t look anything like the picture on the website. Up close the Good Fortune doesn’t look fortunate at all. It looks bedraggled and unseaworthy; it looks like it’s about to sink right here at the dock. I think of a lame cormorant, riding low in the water, awaiting its fate.

Cormorants are different from most other water birds. Cormorants will drown if they don’t dry their feathers. That’s why you see them on a pier or on shore with their dark, dripping wings spread out in the sun and the wind. But they’re the bravest of birds because they are not really at home in the water; they’re not as buoyant as ducks and geese. They’re marginal creatures, living on the edge. They have to work harder to get by.

My father taught me about cormorants. He was a wildlife journalist, specializing in birds. Dad always said he was going to take me on a photo shoot to follow the sandhill crane migration. It was going to be a man-expedition, he promised, an epic father-son trip from Canada to Mexico. We never went.

On the front side of the boat a painted, peeling eye stares at me. A dead man’s stare. An eye that never closes. Is there a matching eye on the other side? I don’t want to look, I don’t want to know.

“What a piece of junk,” I say. “No wonder they call them junks. “Can’t you see it’s a scam? How much did you pay for this, anyway?”

“Don’t be ungrateful, James,” Mother shoots back. “You’re so unappreciative. This is Hawaii. You’re starting your summer adventure in Hawaii. How many kids your age get to do that? You are so lucky!” Orange light leaps out from her head, a solar flare. The intense light triggers the song.

With a yo-heave-ho and a fare-you-well

And a sullen plunge in the sullen swell

Ten fathoms deep on the road to hell

I hear things other people don’t hear.

The dead men sing as they march through my head, the men from the dream. And now the dream is bringing itself to life in the form of this summer adventure program. Somebody’s sick idea of “helping” kids with behavior problems, a sort of boot camp for misfits. Mother found this program on the Internet. Or maybe the program found her, summoned her somehow. She doesn’t know she’s being influenced by people she has never met, some of them dead.

“What’s the matter, James?” Her concern is real, I feel it, little ripples of warmth. But she doesn’t get it. At all. Right now we’re standing side-by-side but we’re worlds apart. Like birds and humans, we merely coexist.

I’d like to tell her what the matter is – but what exactly am I going to say? Mother, the dead men are singing, it’s a bad sign. The boat is a doomed cormorant that can’t dry its wings. That’s the kind of talk that gets me into trouble. She hates it when I repeat what they say; she’s afraid I’m psychotic or something.

“James?” Gone is the false cheerfulness. Now her aura crackles and spits. A Fourth of July sparkler penetrating my skin with hot little darts.

Mother’s face is splotched red from the Honolulu heat. Her once pretty face, now unnaturally fragile, a face stretched too thin, too tight. A face that’s known too many Botox injections, too many interventions, a face carefully composed yet beginning to crumble. Yet even now I can see the blue light of her love for me shining through the veil of disappointment. Disappointment and shame.

I look normal enough on the outside (at least, I think I do) but inside me there’s this, like, hole – a cavity – that I’m constantly trying to avoid. Sometimes I hear my dead father’s voice calling me. James! But his voice doesn’t come from the hole inside, it comes from behind me, and when I hear it my heart flutters. It’s not really him, it’s the echoes of his words bouncing around the universe, never at rest. Then comes the weight of his hand on my left shoulder and the sound of him breathing hard, like he’s been running to catch up. Sometimes when I close my eyes I see his face against the backs of my eyes, like a poor quality video. His lips are moving but I can’t make out what he’s trying to tell me.

Mother’s boyfriend interrupts my thoughts; his voice is a Doberman’s whine.

“He’ll be fine. You’ll be fine, won’t you, kid? Come on, now. Man up!” He reaches out to grip my shoulder but I step back to avoid it, nearly falling off the dock. I’ve hated all my mother’s boyfriends. I know what it is they want and it sickens me.

She smiles, her lips tight. “It’s just – now that we’re here – he seems so young. Compared to the others.”

And now I see them – three guys sitting on the dock at the end of the pier. They’re leaning against new Urban Outfitter gear bags, all sprawled out with their long legs and arms, their hair spiked up with gel. They are cut from the same mold, they could be brothers, they could be triplets.

They’re going aboard with me, I realize. We’re all in the same boat; we’re all going down together. These guys don’t seem to know it, or care. They’re all holding cell phones, making last minute texts to their friends back home, cigarettes hanging from their mouths. I didn’t bring any cigarettes, I don’t smoke. But I did bring my lighter, I carry it everywhere because you never know. I brought my cell phone too, but it’s already dead and there’s no way to charge it on the boat – that’s what it said on the website. I don’t know why I even brought it, except the weight of it, deep in the pocket of my shorts, feels solid. Comforting.

My shipmates have man-legs, I envy them that. . Coarse hair covers their muscular calves like sea grass. Billabong shorts hang low on their hips, they look like some kind of California surf gang. Their feet are all huge in their ragged Converse All-Stars: black, brown, red. These three are the shit and they know it. These fuckers will taunt me, they will make my life miserable; of this I’m sure.

“He’ll be fine. He just hasn’t got his growth spurt yet. Your boy’s old enough, hell, he’s fifteen. Aren’t you, Jim? You’ll be fine.” The Jerk-du-Jour looks at his watch again. His face is shiny, his Tommy Bahama aloha shirt is all creased and damp, and his gut presses against it like he’s pregnant. “It’s not like he’s going off to war. This is just a cruise, a floating summer camp. They used to send kids like him to military school. Kids these days have all gone soft. Now they get to go sailing the South Pacific. Pretty sweet deal, if you ask me, right Jim?” He has the nerve to wink at me, like we’re buds. Like we share a secret. I hate that he calls me Jim.

The truth is I’m here because my mother wants to be rid of me. She can’t deal with what I am, with what I’m becoming. She needs me gone. Not like dead gone, just out of sight, out of mind for the summer. So she and the jackass boyfriend can – ugh – I can’t let myself think about what it is they want to do with each other when I’m not around.

Last summer it was a different boyfriend (I forget his name, I forget all of their names) and the Teens for Christ Summer Camp for me. There I endured six weeks of forced socialization, thrown in with people I had nothing in common with. Of course I was immediately rejected from their group, expelled into the void of oblivion where I remained in orbit around Planet Jesus like a piece of space junk – potentially dangerous but mostly forgotten, a reflected light passing overhead. What were the odds of my re-entry? The resident life forms ignored me. .

But this summer is going to be worse. Much worse.

*

“All hands!” a man bellows through a bullhorn. “Ten minutes ‘til cast-off!”

Was that the captain? His voice reverberates through my bones like the crash of a gong and I nearly piss my pants with fear. This is it. This is where I board the boat, never to be heard from again. Mother bends her head for a kiss. I feel her warm lips brush my left ear as I turn my head away. She touches my shoulder, like she’s afraid of me.

“I’ll miss you, Jamey, honey. Love you!”

I want her to hug me, to be enfolded in those fake-tanned arms. “You don’t have to miss me, Mother. You could take me home.”

She stiffens and a wave of white light shoots from her head, a scorching flame, a solar flare. She is thinking, You ungrateful brat! She’s also singed with guilt. I can smell her guilt like a slice of bread stuck in the toaster, smoke filling the kitchen.

“It’s not every kid who gets to go sailing on a real Chinese junk for the summer,” says the boyfriend, backing her up. Wanting me out of the way. Like he’s the one who paid for it. Maybe he was, for all I know. I don’t think we have that kind of money.

The energy pulsates from her body, so intense I’m afraid she’ll spontaneously combust. Her lips move but the words are drowned out by the dead men from the black hole inside me, chanting that stupid poem again.

‘Twas a cutlass swipe, or an ounce of lead

Or a yawning hole in a battered head

And the scuppers glut with a rotting red

Yo-ho-ho and a bottle of rum…

END of CHAPTER ONE…

Available in trade paperback, electronic and Audible editions wherever good books are sold