There There; Here Now

Reflections of There There, a novel by Tommy Orange (copyright 2018)

Spoiler Alert!

In his novel, There There, Tommy Orange pieces together patchwork narratives of twelve Native Americans as they prepare to attend the Oakland Powwow. Oakland is important as a setting, signifying the aftermath of the Urban Relocation Program of mid-twentieth century, a federal program encouraging Native Americans to move off the reservations and into cities to assimilate and reinvent themselves. The twelve contemporary, “urban Indians” in the novel are all struggling with various personal issues, but they are all trying to discover who they are and where they came from. They are searching not only for their individuality, but for their collective identity. They are looking for their greater family, their tribe.

Some of the characters are dealing with drug and alcohol dependency — not only their own, but their mothers’. Some are trying to prove their manhood, or just survive on the streets. Some of them are searching for their father. Orphaned from their past, their culture, their original land, they are trying to discover what it means to be Indian, in 21st century Oakland. Here, now.

“There is no there there,” wrote Gertrude Stein, speaking of her childhood home in Oakland. The quotation itself expresses a disenfranchisement of Place, a nowhere, an erased past.

Author Tommy Orange pays ironic homage to Stein and other American writers throughout the story. For example, the quote from African American writer, James Baldwin, introducing part III. “People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them” (pg. 157). Including these quotes helps non-Indian readers relate to the disconnection of time, place, and tribe his characters have experienced and are continuing to experience.

Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield is the oldest of the characters. She is a grandmother in the Indian way — that is, she raised her sister’s biological grandchildren. Opal herself, grew up on the edge of poverty with here Indian mother and half-sister Jacquie Redfeather, in East Oakland. She knew her Indian past. “Our mom told us she was a medicine woman and renowned singer of spiritual songs, so I was supposed to carry that big old name around with honor (46). Opal’s mother told her that they should never not tell their stories, and that no one is too young to hear. “We’re all here because of a lie. They’ve been lying to us since they came. They’re lying to us now” (57). Opal, like her mother, is a strong force, loyal to her family. Opal knows her grandsons are afraid of her, as she was always afraid of her mom. “It’s to prepare them for a world made for Native people not to live but to die in, shrink, disappear.” Opal pushes them because “it will take more for them to succeed than someone who is not Native” (165).

Opal doesn’t indulge herself in expressing her inner “Indian.” She is embittered from memories of her own past, and too busy supporting her extended family, keeping them alive and provided for. Ironically, she works for the U.S. government, delivering the mail. Having lived through the Alcatraz occupation, she seems to have given up hope for a real Indian revival. She has not lost her tribal roots but she isn’t doing much to pass them on. Whay she does pass on, perhaps, is her strength and tenacity.

Like the author himself, Edwin (Ed) Black is a writer and a scholar. He earned a master’s degree in comparative literature with a focus on Native American literature, “all without knowing my tribe” (72). With a wry sense of depreciation, he describes himself as a fat, out-of-shape, constipated, unemployed loser, addicted to the internet, where he admits to trying, unsuccessfully, to recreate himself. Despite his education, Ed is unemployed and lives with his mother. Although he has studied Native American literature and culture, Edwin still feels disconnected to his people because he doesn’t know who his father is, or what tribe he belongs to. His mother is not Indian, but she is supportive. On a social media site, Ed pretends to be his mother in order to find his biological father. He finds Harvey, a Southern Cheyenne, who is coming to Oakland for the powwow.

Edwin’s mother urges him to apply for a paid internship at the Oakland powwow. He does, lands the job, and meets Blue, one of the organizers. They seem to have a connection. He tells Blue about a story he’s writing — it sounds very much like a parable of what the Indians experienced, after contact with the Europeans. But Blue is dismissive; she doesn’t seem to make the connection (244-245). Still, Edwin now has a job, a possible relationship with Blue, and to his great satisfaction, he meet his father in person.

While Edwin is disparaging of himself throughout, and even though he is one of the victims of the robbery, he expresses optimism. He uses the word hope “He had hope” (63). “I feel something not unlike hope” (78), “all that I once hoped I’d be” (75), “This is a new life” (243).

Orville, Lony, and Loother were born “heroin babies”. Their mother, an addict, killed herself. Their biological grandmother, Opal’s sister Jacquie, the boys’ biological grandmother, was in no shape herself to raise them, so Opal adopted them. She has been the rock in their lives but it is not enough to complete them. The boys lack a father in their lives.

Each boy has his own personality and his own quest, but fourteen-year-old Orville is drawn to discover his cultural heritage. Orville finds the instruction he needs on YouTube, where he learns how to dance in the Cheyenne way. He thinks his grandmother Opal is not supportive. “Opal had been openly against any of them doing anything Indian. She treated it all like it was something they could decide for themselves when they were old enough. Like drinking or driving or smoke or voting. Indianing” (118).

Orville doesn’t find this supportive. He asks Opal why she didn’t teach them anything about being an Indian. She answers, “Cheyenne way, we let you learn for yourself, then teach you when you’re ready” (119). Orville does learn for himself, through the internet. He manages to find authenticity and connection in the dancing and in donning the regalia. “In that moment, in front of the TV, he knew. He was part of something” (121). Young Orville Redfeather persists and succeeds in finding a way to be authentically Indian before he is shot at the powwow during a robbery staged by other Indians.

There There shows the result of attempts at assimilation and erasure of indigenous culture, of a forced disconnection to one’s people, heritage, and sense of place.

As the characters come together and their narratives unfold, we see how they are related to one another, how they are connected. Although the powwow ends tragically — a symptom itself of the fragmentation and disruption of values within the displaced Native American communities — some of the novel’s characters fight back to reclaim their tribal identity. Although they are victims of the shooting, the lives of Edwin Black and Orville Redfeather reflect the hope that American Indians can reclaim their identity and direct their own future. – Linda Collison, 2020

***

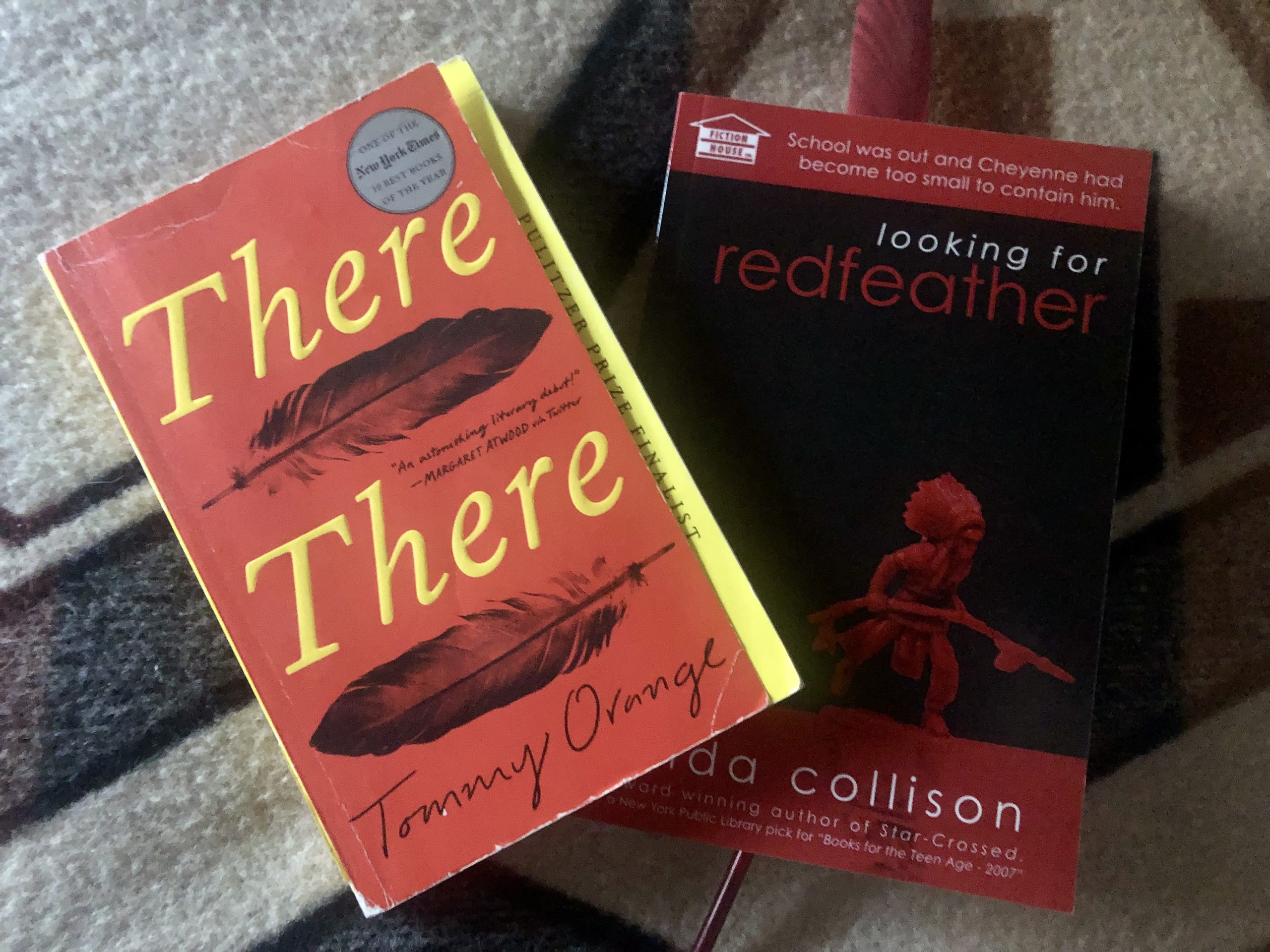

In my novel Looking for Redfeather (copyright 2013) the young characters also search for identity — their own and that of the authentic American Indian Ramie believes is his father. Both novels are available from most bookstores. There There was one of the New York Times 10 Best Books of the Year, and Looking for Redfeather was a Foreword Reviews finalist for Indie YA Book of the Year, 2013.