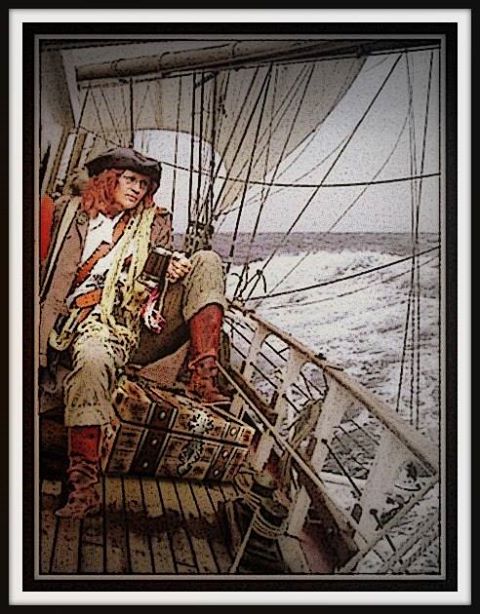

Women in breeches — I got caught up in the masquerade back in 1999, while serving as a voyage crewmember aboard the HM Bark Endeavour, a replica of James Cook’s 18th century ship, which was circumnavigating that year. On my three-week passage from Vancouver to Kealakekua, Hawaii I worked alongside 53 officers and men (one of whom I was married to) to sail, steer, and maintain the ship. Eight of us were female. On this passage of a lifetime, I became intrigued with the idea of a woman dressing like a sailor and doing a man’s job aboard a ship – because that’s exactly what I was doing! I figured if a middle-aged woman could do the work, surely a much younger gal would have no problem.

In spite of the persistent, old husbands’ tale that women are bad luck at sea, women have long been going to sea, luck be damned. But for a period of several hundred years some of them had to resort to disguise.

And for some, it ended badly. From the St. James Gazette, supplement to the Manchester Courier on July 5, 1890 we hear this snippet of a story:

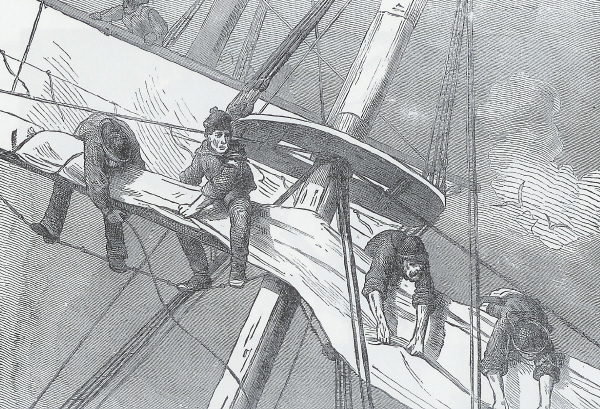

The case of the poor little sea apprentice “Hans Brandt” who the other day fell into the hold of the barque Ida of Pensacola, at West Hartlpool and was killed, adds one more name to the long list of women who, for one reason or another, have put aside the garments of their sex and have donned the habits and imitated the ways of men. Not until “Hans Brandt’s” body was being prepared for burial was it discovered that the Ida’s apprentice was a girl… (britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

From the Renaissance through the Victorian age there are many acounts of women in disguise working aboard ship as sailors, servants, skilled craftsmen, marines –and even a few officers, such as Anne Chamberlyne, twenty-three year old daughter of a lawyer, who served aboard the Grifffin Fireship, commanded by her brother Clifford, during the Battle of Beachy Head in 1690. Most of these femmes fared better than poor Hans Brandt who fell into the hold. Some went on to write their memoirs. Some became immortalized in folk songs. And some, like Anne Chamberlyne, had memorials errected in their honor.

The first books I came across that were entirely devoted to women at sea were Joan Druett’s Hen Frigates, and She Captains; Heroines and Hellions of the Sea. I soon discovered many other works, but Joan’s books introduced me to the world of women on ships. Another of her books on the subject is Petticoat Whalers; Whaling Wives at Sea, 1820-1920. Over the years I’ve collected many more sources. Historians Lesley and Roy Adkins, authors of several British Naval history books, have been very helpful in sharing their own research with me.

Just as I was writing this post, Andrew Beltz, one of the crew aboard “All Things Nautical” Facebook group gave me a hot tip about Louise/Louis Giradin, a French woman who masqueraded as a steward on La Recherche, which set out 1791 under the command of Bruny d”Entrecasteaux, in search of the missing La Perouse.

“She had appeared at Brest disguised as a man, with a letter of introduction to Mme Le Fournier d’Yauville. She persuaded her brother Jean-Michel Huon de Kermadec, then second in command to d’Entrecasteaux, to recommend her as a steward on the Recherche. It appears that d’Entrecasteaux knew her secret, and gave his approval… She had a small but separate cabin… During the voyage, Girardin maintained a male identity, despite widespread suspicion. She even fought a duel with a crew member who questioned her gender… “ from — Journeys of Enlightenment

While Louise Girardin is honored with a plaque in Tasmania, few scholars have given serious attention to the many women soldiers and sailors of the pre-modern era. Not many fiction writers have given life to their stories, either. Crossdressing women on ships seem to be regarded by many historical novelists as unwanted intruders into the male domain of wooden ships. Why can’t the damned dames just stay home, card wool, and mind the starving brats? OK, maybe there were a few of these broads in breeches (obviously lesbians) — but NOT on my ship, dammit! Julian Stockwin includes a crossdressing stowaway named Pookie in one of his Kydd adventures, but for the most part, they are shunned.

But crossdressers were once objects of admiration. Beginning in the Elizabethan era and continuing through the 19th century, stories and songs about young women gone to war on land or sea, were popular among the working classes of Great Britain and North America. According to Dianne Dugaw, these folk songs were as well-known in their time as Blowin’ in the Wind was, in the 1960’s. The female soldier or sailor was an enduring motif – a character who displayed both male courage and female fidelity. In most of these ballads (Dugaw cites hundreds of them) the theme is that of a virtuous woman gone to war in search of the man she loves. This heroine captured the imagination of the public for hundreds of years but died out in the twentieth century, as women’s rights became more of an issue — and perhaps more of a threat.

“But how did they get away with it?”

I can only throw out some educated guesses based on my own experience and what others have to say on the matter.

As Joan Druett, Suzanne Stark, and other nautical historians have pointed out, there were many young boys serving aboard these ships. A female in breeches might easily pass as a teenaged boy. We’ve all seen such epicene youngsters in that awkwardly beautiful stage of development; people who could be either male or female, we can’t be certain.

Before the twentieth century the navies didn’t require thorough physical exams. The only time seamen were required to strip was if they were about to be flogged. The navies needed capable men — especially when a war was on, which was much of the time in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. If someone presented themself as a man and was dressed like a man, and gave a man’s name – why, he would be welcomed aboard, no questions asked. Who cared if he had a smooth cheek and a soft voice? Ample breasts are easily flattened. Loose breeches rather than tight ones would hide what wasn’t there. My fictional crossdresser Patricia/Patrick MacPherson is by nature flat-chested with boyish hips and a complexion ruined by freckles. It’s only her voice she has to work on. After a time it becomes second nature.

Having lived and worked aboard the Endeavour Replica, I can tell you that seamen are kept busy most of the time and people aren’t lurking around corners waiting for you to flash your undergarments or to see what’s hidden inside them. Eighteenth-century ships were ill-lit and extremely dark belowdecks, even during the daytime. People didn’t bathe often; they seldom changed their clothes. Women likely held their bladders until after dark before relieving themselves in the heads, or the “seats of ease.” People in crowded places, such as ships, tend to respect one another’s privacy. As sodomy was punishable by death, men likely tended to keep their eyes and hands to themselves, once they sailed away from the prostitutes who came to the ship by the boatloads when the ships were at anchor. Then again, the warrants could take their wives to sea with them –the ship was their home –so 18th century ships were not the exclusive male clubs some novelists make them out to be. There were women on many ships and maybe some of these warrant’s wives recognized and helped their sisters in disguise.

What of menstrual periods, some ask me. If you’re a squeamish male, you might want to skip the rest of this paragraph. Well, what of it? I mean, can you walk into a crowded room today and pick out the women who are menstruating? I doubt it. There were rags — and there was oakum, the fibers of worn-out ropes picked apart and collected to reuse as caulking. Pretty scratchy, but it might work in a pinch. Beause many of the seamen suffered from constipation and bleeding hemmorhoids, blood-stained breeches would not draw much notice – and the stains could be covered up with tar, plentiful on a ship. Then again, amennorhea may have been the rule. The Mayo Clinic lists stress, low bodyweight and excessive exercise as conditions which can cause the cessation of menstruation. Due to the hard work and limited diet, women posing as men might have skipped menses or have had very light flows, easily contained. OK squeamish males, you can start reading again.

Maybe some of these masquerading women had sponsors – men or women aboard who knew their secret and helped them get by. Maybe they were friends or lovers on land. Maybe the sponsor felt compassion for them. Maybe they admired them. Then again, maybe some of these women were coerced into giving sexual favors in return for guarding their real identity.

In The Discovery of Jeanne Baret (Crown Publishers; 2010) Glynis Ridley suggests that the the crossdressing Jeanne who went on Bougainville’s expedition as the botanist Commercon’s assistant, was gang-raped by some of the crew on the island of New Ireland, and subsequently became pregnant, delivering the baby on Mauritius, where she remained for seven years before completing her circumnavigation. Ridley’s interpretations of the accounts of Bougainville and his officers, is a dark and chilling one. I don’t always agree with the conclusions she comes to, but the case she presents is plausible. Although in Ridley’s interpretation it wasn’t the sailors who gang-raped Baret, but the other servants and possibly, the ship surgeon.

So why did they do it? The paycheck was of course, the big draw. Always in arrears, the pay was likely more than a femme sole could make selling fish — or selling her favors. The roof over her head, leaky though it might be, was a nice perk. As were the three square meals of weevily ship buscuit , mouldy cheese and salt beef. A ration of grog and a hammock to sleep in? And aboard a naval ship, the chance of prize money, which was divided among the crew! Are you kidding me? Who wouldn’t sell a ragged petticoat and go to sea?

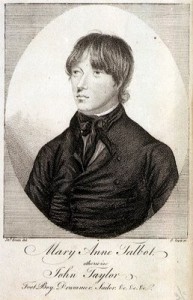

But some females were coerced into the role of cabin boy by their masters. Mary Anne Talbot, for instance. Talbot’s master was militia captain Essex Bowen, who assigned her with boy’s clothing, the name of John Taylor, and brought her along to the West Indies as his personal servant. We can only imagine the many tasks she was required to perform for him… Another reported case is that of thirteen-year-old Rebecca Ann Johnson whose father dressed her as a boy and apprenticed her to a collier ship where she served four years.

But surely a few girls went to sea primarily for the adventure, as I did aboard Endeavour.

How many? We’ll never know. How did they get away with it? We can only surmise. What I can tell you for certain is that a woman can do a man’s job aboard a sailing ship. I did it, and I earned the respect of my male watchmates, whose knees trembled as much as mine the first time we climbed up the ratlines, up and over the futtock shrouds, on up to the cross trees and out on the foot rope to make and furl sail. When no sail changes were required, we were put to work doing ship maintenance, which was never-ending. And when, after four hours on watch we went below, we strung up our hammocks and collapsed from fatigue.

In summary, some crossdressers had inside help — someone who knew their secret and helped them — or forced them — to maintain their ruse. But I believe a few enterprising females acted independently, deftly pulling the wool over their shipmates’ eyes. I base this on a phenomenon I call “male pattern blindness” or “androgenic visual deficit.” Many ordinary objects are totally invisible to men who have this genetic trait, which has reached epidemic proportions in the twenty-first century. Maybe you know someone with this handicap? Someone who goes to the refrigerator for a bottle of beer but literally can’t see it lurking behind a jar of mayonaise, and calls to his wife, asking for help?

Having lived and worked with men, both at sea and on land (and having found countless bottles of invisible beer in the refrigerator) I think I know how a women could get away with it. Dress like a man (or a mayonaise jar) and pull your weight. Do your duty, don’t cause trouble, and chances are good your watchmates won’t see past your seaman’s slops and your sunburned, tar-smudged face. Apparently it worked for Hans Brandt — but watch out for open hatches.

In future blogs I’ll share more of my personal experiences as an ordinary seaman aboard HM Bark Endeavour — and I’ll discuss individual crossdressing seamen in more detail.

By a Yankee Moon, a novel about a crossdressing sailor and book three of the Patricia MacPherson Nautical Adventure Series, will be available in 2014. Barbados Bound and Surgeon’s Mate, the first two books in the series, are published by Fireship Press.

For more nautical posts please visit the rest of the fleet on this week’s blog hop, organized by Helen Hollick, author of Sea Witch Voyages, a pirate-based fantasy, and other historical fiction. A rising tide raises all ships!

![2013-Nautical-Blog-Hop-small[1]](http://www.lindacollison.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/2013-Nautical-Blog-Hop-small1.jpg)