Fiction writers: What motivates your protagonist?

Fiction writers: What motivates your protagonist?

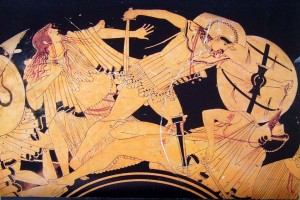

Hand of Fire tells the tale of Briseis, the captive woman Achilles and Agamemnon fought over in the Iliad. When Achilles, the half-immortal Greek warrior, takes Briseis captive in the midst of the Trojan War, he gets more than he bargained for: a healing priestess, a strong-willed princess—and a warrior. She raises a sword against Achilles and ignites a passion that seals his fate and changes her destiny.

What makes a young woman pick up a sword against a powerful Greek Warrior? I asked Judith Starkston, author of Hand of Fire, to tell us something about how she writes believable action in historical fiction. What makes Brisius, her young female protagonist, pick up a sword against Achilles, and how do you convince the reader of this heroic action?

Starkston says:

“A while back Justin Aucoin had a great guest post here on sword fighting. I commented that I wished I knew more about sword fights, but that mine were Homeric and thus somewhat different from his descriptions. Linda asked me what my favorite Homeric fight scene was and I somewhat jokingly said, the one where my heroine takes up a sword against Achilles (apologies to the bard—no such scene in the Homeric corpus—I made it up). She invited me to write a post about that scene. I’m focusing on motivation—why Briseis lifted that sword—since I can claim no expertise in actual sword fighting technique the way Justin can.

In Homer’s Iliad Briseis has only a few lines. She is the captive woman Achilles and Agamemnon fight over and as such she is central to the action of the poem, but we only learn a tiny amount about her. We know she is a princess from the city of Lyrnessos, which is one of Troy’s allies, that she had three brothers, and that she loved Achilles even though he took her captive and seemingly ruined her life. I decided to write a novel filling out her life and world. And in the course of that story she challenges the greatest of the Greek heroes with a sword.”

Why did she take up a sword?

“If she were a warrior princess, the sort we often find in fantasy novels or in history through women like Britain’s Boudica, that would be easy to answer. But the Briseis I got to know was no warrior. I researched the recently excavated world of the Bronze Age in what is now Turkey where Troy was situated and found a model of the person I thought she might well have been in the ancient Hittite hashawa, a kind of healing priestess, literate and respected. The Hittites and culturally related peoples lived throughout this region. I found powerful women in this culture, both the healing priestesses and queens who continued ruling after their husband’s deaths and whose counsel was accepted as equal to the king’s. As both a princess and a hashawa, Briseis wielded power, but there were no examples of women who fought battles or took up arms. As a healer, she opposed taking her people into the Trojan War because she knew up close what danger to the human body truly means. In my novel she spends her time and emotional focus curing people and trying her best to protect the Lyrnessans from her husband’s rash desire to fight Achilles at any cost. She is the most unlikely candidate for fighting with a sword against the half-immortal hero.

So why does she do it? For the most primeval and basic of reasons. She is driven to protect her family, in this case her youngest brother, whom she had been especially close to throughout her childhood. She has no battle training and she doesn’t carry on as a warrior from that day forth, but in a moment of love-driven rage she grabs a sword that chance has laid at her feet at this critical moment. She defends her brother, whose character we already know as sweet and unwarriorlike, because for her there is no choice, no alternative. The wild sound of fury like hundreds of bees swarming in her head and the utter unwillingness to accept that she is helpless to protect her brother drive her more than self-preservation.

That’s not difficult to understand as motivation, but it only works if the character herself has enough courage and inner strength to take on such a daunting challenge, to feel no alternative. Many of us would see our brother or sister in danger and be unable to act with sufficient force. Interestingly enough, I knew fairly early on in the drafting of this book that this moment of confrontation would be central to the novel, of sword upraised defensively against the most powerful sword in legendary history. But it took me a while to find the solid core of Briseis’s strength and how to depict it. Briseis had to keep redirecting my efforts and showing me how to reveal inner resolve. She had to embrace violence and accept its inevitable place in her fractured world. I had a very hard time giving in to that. I kept shielding this young woman when she simply didn’t want to be.

Eventually a woman strong enough to challenge Achilles—and eventually to love this impossible hero—came forward, from the historical record and from my struggling imagination.”

Here’s a short passage from a fight scene in Hand of Fire:

(Brisius) stopped. A shadow had fallen across the opening. The guardsman sitting on the well drew his sword. Iatros pushed her down so she was hidden behind the well and drew his sword. She heard the sounds as bronze-nailed footsteps rushed. Swords clashed. A man fell.

Then a voice called out in Greek, “Lord Achilles, come over—” There was a grunt, a thud. The voice fell silent. A Greek warrior lay against the well. His hand loosened its grip on his sword.

She lifted her head to see over the well. Iatros stared at his bloody sword and the dead Greek. The man with the leg wound was on the ground, his sword arm still outstretched, but his innards poured out onto the hard dirt.

Other guardsmen came out of the stables, but it did not matter, for the gate filled with a huge form, and Achilles plunged toward Iatros. Her brother lifted his sword to meet the oncoming stroke. A rage rose up in her; the sound of a hundred bees filled her head. In one motion she swept the dead Greek’s sword off the ground and leapt from behind the well. Achilles’s blade flashed in the air above her. She saw his hands grasping the hilt and sensed their power, then saw his look of astonishment as she raised her blade against the blow aimed at her brother. A new, invincible strength coursed through her arms. The desire to strike—raw and terrifying—drove out her helplessness. Her blade met his. A bolt shot through her, and she reeled from the force. Achilles jerked his chest backwards even as the momentum of his swing carried him forward. Achilles’s sword cut through the unprotected joint of her brother’s armor between the neck and shoulder. Iatros’s head fell to the side. As the weight of Iatros’s body carried her to the ground, she heard an anguished cry and could not tell if it was hers or Achilles’s…

Judith Starkston writes historical fiction and mysteries set in Troy and the Hittite Empire, as well as the occasional contemporary short story. She also reviews books for Historical Novels Review, the New York Journal of Books, the Poisoned Fiction Review, and on her own website. Hand of Fire, will be published by Fireship Press on September 10, 2014. More about the historical background of this period, as well as historical fiction reviews can be found on the author’s website JudithStarkston.com. Follow her on Twitter @JudithStarkston and on Facebook .