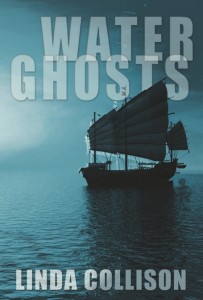

Water Ghosts took a long time to write, mostly because I got side-tracked with historical research, including Chinese maritime navigational techniques, Asian gods, goddesses, and ghosts — and court eunuchs during the Ming Dynasty.

If you’re a Game of Thrones fan, you might think of Varys when you hear the word eunuch. But what exactly is a eunuch?

A eunuch is a castrated male. That is to say, his reproductive glands have been removed or rendered inactive, much as we neuter horses, dogs and house cats.

Why did they do it?

Castration was done for various reasons but the purpose was to de-power males. To remove their ability to impregnate and procreate. It was often done to young boys, against their will. Castration was sometimes used to emasculate prisoners of war and to form a class of servants who would not be able to impregnate the women. Young eunuchs could be raised as the master desired and they were unable to knock up the ruler’s “property.” Men in power have always had to worry about who was sleeping with their wife or concubines and whose babies those women were really carrying. Men who abuse power can rape and castrate in an effort to manipulate not only those around them but to ensure their own genetic material gets passed on.

Eunuchs are not exclusive to imperial China. The ancient Assyrians, Sumerians, Persians, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, and Ottomans all castrated young males as punishment and for court service. A few societies emasculated young boys to keep their voices from changing, for singing purposes. These castrati are known to have existed from the Byzantine empire.

The eunuch Narses was a successful general under the Byzantine emperor Justinian. In fact, many eunuchs excelled as military leaders (See Wikipedia list of notable eunuchs.)

Yet the practice of castration was developed to a fine art throughout the long history of imperial China and became deeply entrenched in court culture. At the end of the Ming dynasty there were said to be 70,000 eunuchs!

Sun Yaoting the last imperial eunuch, died in 1996.

In China castration didn’t just remove a male’s scrotum — the knife took his penis too. Those who survived were deformed, humiliated, and plagued with incontinence. They had to use a plug to keep their urine contained. In spite of the trauma, many eunuchs went on to achieve notoriety. One such violated man was Zheng He, who rose to become a powerful admiral in the Yongle Court during the early Ming Dynasty.

Zheng He (a contemporary of Christopher Columbus) was born in 1371, with the name Ma He. Born Muslim, he became dedicated to Mazu (also called Tianfei), Chinese goddess of seafarers. (As I began to read about the eunuch mariner I also began to learn about the Chinese pantheon, which includes an impressive array of gods, goddesses, deities, demons, and ghosts who direct or in some way influence the lives of millions of people, even today.)

The boy named Ma He was captured by the Ming army during the war in which the Mongols were defeated and his father was killed. He was castrated and sent to serve Prince Zhu Di, at first in the household and then as a soldier on the northern frontier. Ma He, renamed Zheng He, earned the young prince’s trust and later helped him usurp the throne to become emperor. The eunuch was made admiral, in charge of seven naval expeditions and in command of a fleet of ships to establish a Chinese presence and impose control over Indian Ocean trade.

These Chinese-built ships were enormous — larger than any wooden ships ever built in the history of the world — and are often referred to as the treasure fleet. Their primary purpose wasn’t to carry conquering armies, but instead to collect “tribute” from the societies they visited. The not-so-subtle message was, bow down to us, fill our holds with the best you have to offer, acknowledge us as your superiors — or else!

The very first of these voyages may have been part of the usurper’s attempt to capture Jianwen, his predecessor who may have escaped. I made use of this supposition in Water Ghosts, which is really two stories: that of young James and the eunuch Yu, who lived more than six hundred years earlier.

I don’t make this stuff up! Well, some of it I do. But there is a lot of truth behind the fiction. My copy of Louise Levathes’s marvelous book, When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405-1433, is heavily dog-earred and underlined, as is The Eunuchs of the Ming Dynasty by Shih-Shan Henry Tsai. And there were many more sources.

Water Ghosts is a contemporary adventure, a psychological study, and a ghost story — but that’s only the tip of the iceberg. Beneath the water’s surface lies the unseen bulk of history that supports it. I hope readers connect with James and with Yu, the teenaged eunuch ghost who is trying so desperately to take what James has.